To over simplify it, there were several aspects.

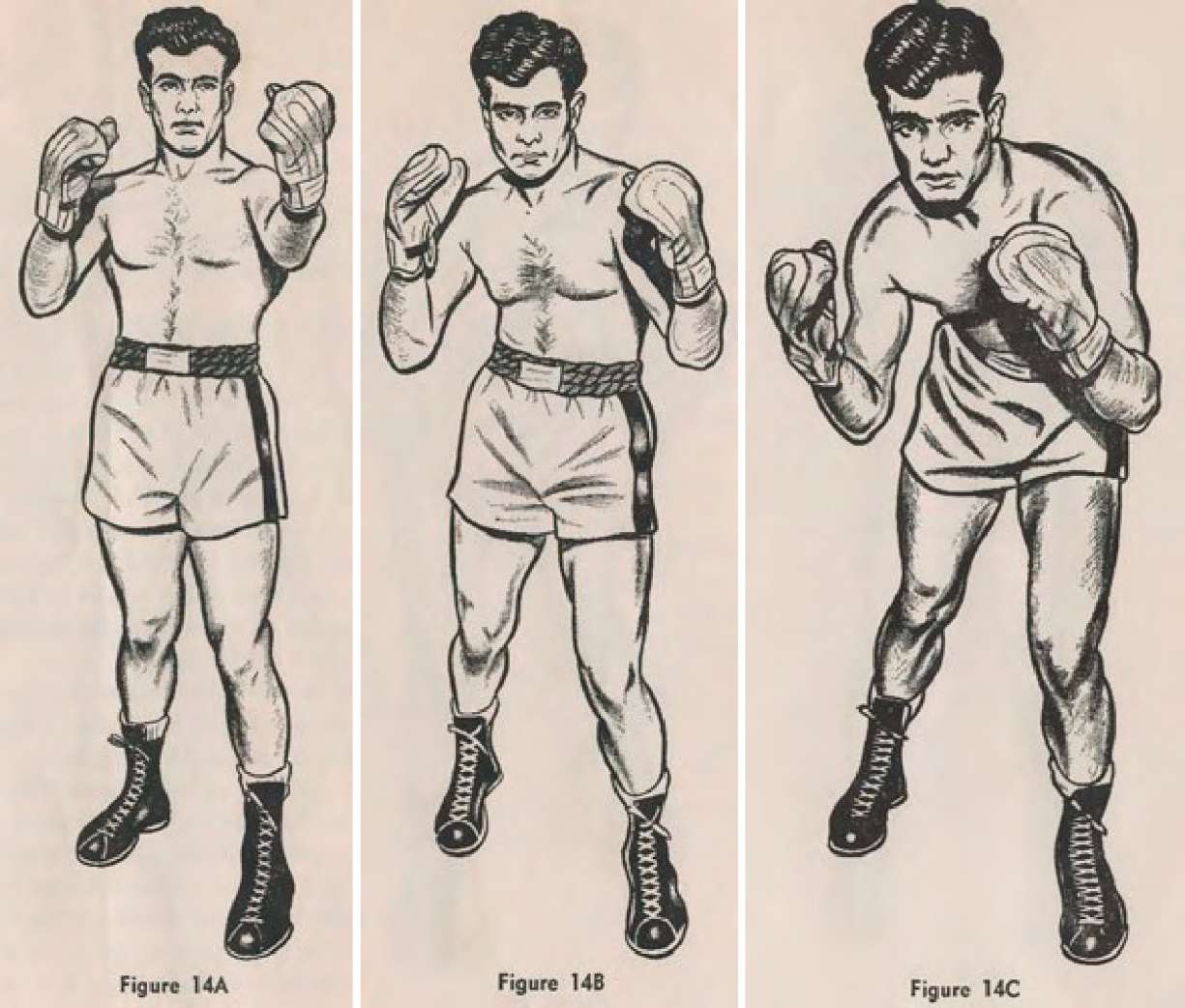

First, the inclusion of stand-up grappling, tripping, and throwing tended to force striking ranges further out. If fighters got in close enough to use, for instance, a modern hook, one of them was grabbing the other and attempting to throw them. Throwing was a very highly sought after spectacle in Broughton and LPR style boxing. The fans absolutely loved it and were particularly fond of any variation of the Cross-Buttock (a hip-toss usually). If you didn't want to grapple, or wanted to control when or how to your benefit, you pushed out the range. Pushing out ranges means more linear punches and more time to see a punch coming and successfully block it.

Second, the lack of modern gloves was a factor in pushing out the range. Gloves (mittens/mufflers) were only used in amateur matches or only in training sessions by professionals. Prize Fighting was strictly no glove. In fact, Prize Fighters were known to speak derisively about the use of gloves in official matches. Even when gloves were used they were very small, light, and hard by modern standards. Interestingly, the gloves used at the time were not particularly prohibitive of successfully grappling & throwing. Additionally wraps were unheard of. The type of gloves used and the lack of wraps offered less-to-no protection against boxers fractures. To protect the hands, boxers of the time were more likely to use a pistol-grip punching technique. These two elements together tended to encourage ranges to push out to a fairly distant out-fighting range for punches.

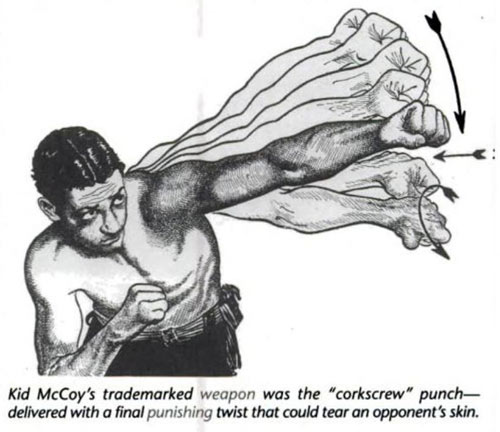

Third, there was often a derision for circular punches and a preference for linear punches. While circular punching did exist (such as the "rounding blow" which figures prominently in Mendoza's lessons) it was often derided as a unskilled an unsophisticated "swing." Particularly in the LPR and follow on era (before MoQ was fully accepted), many Prize Fighters believed that only untalented or poorly trained boxers used "swings" while straight blows such as the Left Lead or Lead-off and the Straight Rear, were considered precision blows and the mark of a skilled boxer. This position is most clearly stated in "The Straight Left and how to Cultivate it" (you can download the PDF free from my lulu site).

Fourth (though not last), Broughton and LPR rules had no limits on the number of rounds, the length of rounds, nor even the length of a match. Matches lasting dozens or even hundreds of rounds were common, and they could go on for hours (or even more than a day in at least one case I found). Prize Fighters were in it for the long haul. Getting thrown to the ground, particularly on the surfaces they were wont to fight on, was very degrading on the boxer's performance and ability. And getting pummeled by punches was also very degrading to the long term performance. Punches that land add up. One famous match had the odds-on favorite (and more famous) boxer losing because of taking "Choppers" (a kind of downward striking back-fist or hammer-fist) to the eyes and nose. Both of his eyes closed up and he was fighting blind. Unsurprisingly, he lost. In order to avoid the short term punishment and stay in the fight for the long haul, boxers wanted to be at as far a distance from their opponent as reasonably possible in order to see, and prevent, as many punches and grapples as possible, while still being close enough to throw their own punches or grapple if they wanted.

As the MoQ rules became more and more accepted, removing the incentive of grappling, adding time limits and round limits, and slowing adding more protective gear (gloves and wraps), the worries about long-term fights became less, the possibility of scoring true knock-out blows became greater, and the viability of no-grappling in-fighting techniques became more and more clear, the need for extended out-fighting positions fell and with it the viability of blocking techniques.

There's more detail and fleshing-out which can be done, of course. A whole book could be written just around the social condemnation of pre-MoQ boxing, how MoQ was partially intended to "civilize" the art and make it socially acceptable, and what the consequences to the sport's techniques were. But this should be a decent enough 50,000 foot view.

Peace favor your sword,

Kirk