I like this observation. In other systems, the school or the gym, shows what other students can do after training. I think it's more important to show the results of the students than to show the ability of the teacher. To encourage students, I would tell them that I would put them in the promotional videos if they do Jow Ga when sparring. No one gets posted for doing basic kick boxing. Those were the rules.The same issue also happen in the Taiji community. A teacher can make his students to bounce up and down. A student will never make his Taiji teacher to bounce up and down. Why?

Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

Style variation

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Aikido.. The reality?

- Thread starter JowGaWolf

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

I have never seen any Aikido (or Taiji) video that a student apply technique on his teacher. You will assume that a teacher should produce good students.In other systems, the school or the gym, shows what other students can do after training.

Here is a picture of a student (my wife) who throws her teacher (me).

Here is a clip that a student applies head lock on his teacher (me).

I think alot of what we see as "Borrowing and blending" with an opponent's energy is Fake and completely inaccurate. I believe that both exists, but not in the way that it is often demonstrated. If you want to see accurate examples of "Borrowing and blending" with an an opponent's energy then watch people who actually use it.Of course, like in Taichi, there are some frauds. But the concept of borrowing and blending with an opponent's energy is not so foreign or novel a concept: it exists in all martial arts and undeniably has practical application. You just need to know: 1) the energy of a real, resisting opponent. And, 2) What to do when the opponent doesn't give you energy to play with.

Demos are great to watch, but the proof is sparring. Not trying to be disrespectful, but if your skills are this good, then it would be easy to sign up and win Push hands competitions and wrestling competitions. Or at the bare minimum on strangers

One of the things I often took advantage of is demonstration Jow Ga on non-students. This gives people an accurate idea of my ability at the minimum. One day I was training in the part and a Father and Son saw me training. The father was TMA fan. His son was an MMA fan. So I asked his son, what does he like about MMA. His son was a big teenager. So I gave the son an opportunity to take me down. My purpose wasn't to show the son that he couldn't take me down. My purpose was to show him that his idea of how he saw MMA wasn't as easy as he thought. So we get into the ready position. I told him I would not resist. I got into a low fighting horse stance. The son didn't try to take me down. I ask him, why didn't he try to take me down. He said because I was too low.

I enjoy doing things like this because it pokes holes in the assumptions that people have about TMA. They sometimes expect to see magic but are more impressed when they see it's not magic. His son didn't join the school that day, but his dad was able to walk away with bragging rights for his passion about TMA lol. If I only demo against students then people will say that my students let me.

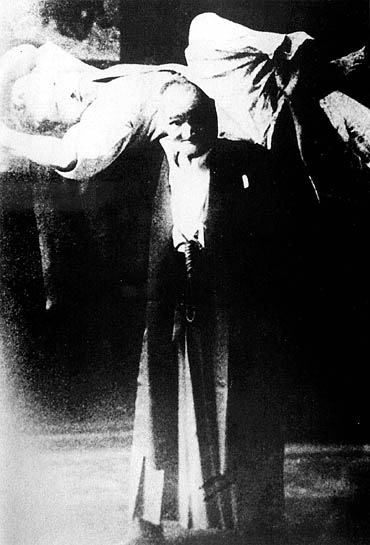

That's a wild picture there.I don't think most Aikido lines do, but the parent art, Daito ryu certainly does. This is a picture of Morihei Ueshiba's teacher, Takeda Sokaku:

That's a wild picture there.

That's a wild picture there.

I would like to see if his student can throw him around like what he does.

I would like to see if his student can make him to bounce back like what he does.

I would like to see if his student can make him to bounce back like what he does.

Last edited:

Steve

Mostly Harmless

Hold on. Did the kid actually have some mma training? I lost the point of the story. What did you actually prove to them? Because it sounds like you intimidated a kid with no training, which doesn't seem all that significant.I think alot of what we see as "Borrowing and blending" with an opponent's energy is Fake and completely inaccurate. I believe that both exists, but not in the way that it is often demonstrated. If you want to see accurate examples of "Borrowing and blending" with an an opponent's energy then watch people who actually use it.

Demos are great to watch, but the proof is sparring. Not trying to be disrespectful, but if your skills are this good, then it would be easy to sign up and win Push hands competitions and wrestling competitions. Or at the bare minimum on strangers

One of the things I often took advantage of is demonstration Jow Ga on non-students. This gives people an accurate idea of my ability at the minimum. One day I was training in the part and a Father and Son saw me training. The father was TMA fan. His son was an MMA fan. So I asked his son, what does he like about MMA. His son was a big teenager. So I gave the son an opportunity to take me down. My purpose wasn't to show the son that he couldn't take me down. My purpose was to show him that his idea of how he saw MMA wasn't as easy as he thought. So we get into the ready position. I told him I would not resist. I got into a low fighting horse stance. The son didn't try to take me down. I ask him, why didn't he try to take me down. He said because I was too low.

I enjoy doing things like this because it pokes holes in the assumptions that people have about TMA. They sometimes expect to see magic but are more impressed when they see it's not magic. His son didn't join the school that day, but his dad was able to walk away with bragging rights for his passion about TMA lol. If I only demo against students then people will say that my students let me.

The purpose of me posting the video was to show how Borrowed Force and Blending Flow works. I specifically showed the child so that people can see this stuff isn't magic that needs 10 years of training to achieve. Borrowed Force and Blending as nothing to do with your opponent's skill level. It's still a skill set regardless of how advanced or inexperience your opponent is. It is not your fault or concern if your opponent is not as good as you.Hold on. Did the kid actually have some mma training? I lost the point of the story. What did you actually prove to them? Because it sounds like you intimidated a kid with no training, which doesn't seem all that significant.

Borrowed Force and Blending Flow seen with older wrestlers. Point of the story. If you really want to know Borrowed Force and Blending then learn from people who actually use it.

Windows is a proprietary os. You use what they give you, and you can't alter anything

Windows is a tma.

Linux is open source, fully customizable and you can alter and recompile any code.

Linux is mma

As a Linux user who prefers TMA, what does that make me? XD

Though, I do get annoyed sometimes with the rigidness of TMA, so I can't argue the comparison!

I have never seen any Aikido (or Taiji) video that a student apply technique on his teacher. You will assume that a teacher should produce good students.

Funnily enough that is one of the very unique things to Daito ryu and Aikido - traditionally in Japanese martial arts the teacher takes the role of uke. Takeda reversed this; he was by all accounts a hyper-paranoid, cantankerous old guy, who would never let anyone throw him.

O'Malley

2nd Black Belt

Yes, koryu weapons folk tend to scoff at aikido weapons work (wasn't that Mochizuki?). In saying 'aikido is an empty-handed art', are you saying that the overhand chop/sankyo techniques (not to mention ikkyo etc) are supposed to be empty handed defenses against people overhand chopping at the top of the head? I've always heard that the aikido/DR theory stressed that these were symbolic of weapon defense and retention?

I remembered that other quote from Mochizuki but couldn't find it (readily) online

In Morihei Ueshiba's aikido, uke does not do the overhand chop in basic techniques. Tori initiates with a metsubushi strike to the face, which leaves uke in the position where ikkyo can be applied. Morihiro Saito spent his life teaching it that way and some gave him crap with the whole "there's no attack in aikido" mantra. Then someone once brought him a technical instruction manual realised under the founder's supervision, where the technique was done Saito's way. As you could imagine, he was beaming, and from then on he'd bring the book with him at seminars and show people, like "see? I'm not making that up!".

I've seen ippondori (a DR technique resembling aikido's ikkyo) done against a downward sword strike in a DR video. However, both DR and aikido techniques are done (and taught) empty handed. Ueshiba had no formal training in weapons (apart from his bayonet training while in service, and he was very good at it) and there's no record of him ever fighting someone while being armed himself.

The weapons retention theory is most likely a rationalisation by later generations to explain why their techniques don't work in hand-to-hand combat.

As you explore Aikido, something has come up as an undercurrent in this thread, and has come up before in threads about Aikido in particular. It's simply that the secret to making Aikido work is to start by already being a competent fighter. In the past, this has been acknowledged by people who trained in Aikido. Point is, maybe the thing most Aikidoka are missing is a prerequisite expertise in one or more other styles, like Judo, BJJ, MMA, Wrestling, Sambo, Savatte, etc.

I think that it's true that most aikidoka today couldn't make it work without experience in the styles you cited. I also think that, historically, this was not the case. World class martial arts practitioners (Kenshiro Abbe, Minoru Mochizuki, Shoji Nishio, Kenji Tomiki, etc.) went to study under Ueshiba whose only significant training was "aikido" (that is, DR). Plus, among Ueshiba's famous "fighters", several had little to no previous martial arts experience (people like Tohei and Shioda had done some judo in highschool, while Tadashi Abe started aikido at 16 with no experience, for example).

Given that Ueshiba and his students gained pretty impressive functional ability from their aikido training, it's worth asking oneself what they were doing differently. Ellis Amdur provides some interesting leads here: Great Aikido —Aikido Greats – 古現武道

Here's an example: We are talking about Aiko. Where did I start? Not with some wrist lock, but some simple concepts.

1. How does Aikido stand

2. Whats the benefit and disadvantage of standing like that.

3. I took a look at the "Aikido chop" and tried to understand what it was being used for. Was it a real strike? Can it be a real strike? In the process of that I saw a difference in how people move their feat or use their forearms. I started noticing differences.

4. I took a look of exercises to see how they were warming up and to get an idea of what parts of the body they are getting into shape.

I listen to how other people explain it. What are the differences and what are the similarities. The fact that he asked BJJ to see if they can "make the techniques work" pretty much tells me that he didn't explore beyond that 2nd layer.

This is a good way to understand the techniques from an external perspective and pinpoint similarities. Yet, without a solid technical foundation (gained through extensive training under a good teacher, and ideally supported by technical material from all-time greats) you'll likely miss the why of the movements. I also feel that solid historical knowledge about the art is useful to avoid baseless interpretations (like the weapons retention argument above).

In order to understand aikido, one has to understand fundamental principles like irimi: “Irimi,” by Ellis Amdur – Aikido Journal

Anyway, if you want to analyse aikido techniques that are as close to their original form as possible (although aikido is not about technique) I recommend looking at the Iwama (under Morihiro Saito) and Yoshinkan (under Gozo Shioda) lines of aikido. They are all-time authorities in terms of technique (although in his later years Shioda's demos shifted from techniques to body principles, which is actually good in terms of aikido).

Shioda could also pop your head out of alignment to make you fall, daito-ryu style (the whole video is good in terms of body movement, but the moment I've just mentioned is around the 2.40 mark):

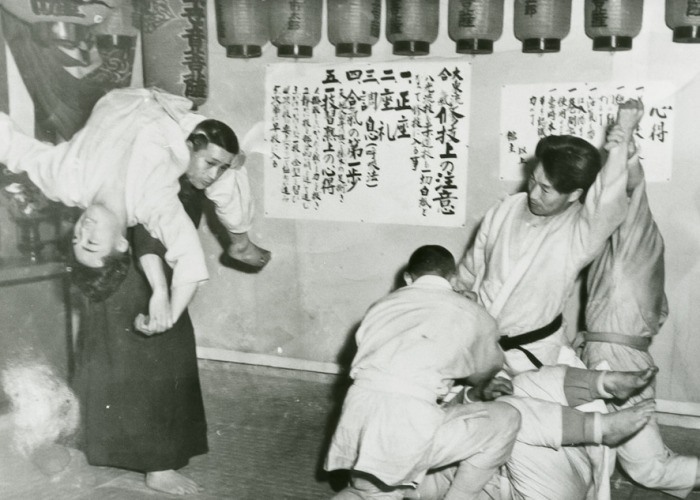

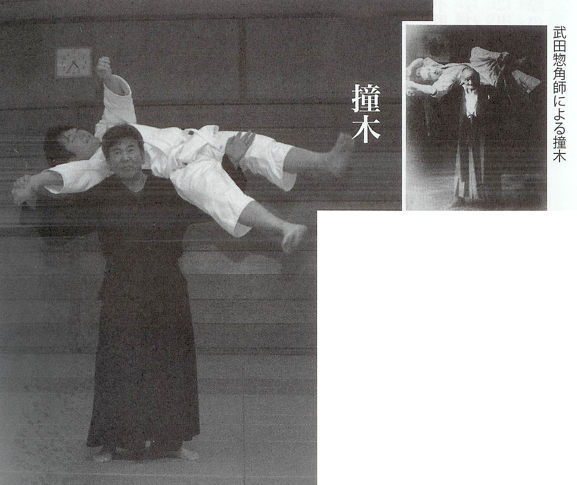

Do Aikido guys use firemen's carry technique?

Yep, it's in daito ryu. We also have it from the back:

Unfortunately, these techniques are trained less and less. I've never done ganseki otoshi because nobody in the dojo would be able to take the fall.

Aikido, for being such a soft art and focusing on borrowing/blending with the opponent, lacks sensitivity training that teaches you how to actually do that against an opponent who is active and resisting. From my point of view, the art itself is valid and valuable, it just doesn't teach one how to adapt when things don't go according to plan, and/or the opponent resists in a way that training partners don't normally do. There are many kind of energies that one has to learn to blend with: committed, uncommitted, soft, tense, etc., and Aikido as typically practice only deals with "soft and committed" energy.

Agreed. According to the art's founder, aikido's purpose is "takemusu aiki" or spontaneous martial technique. Yet, aikido is one of the less spontaneous existing martial arts (and this also goes for lines like Iwama style that purports to stick closely to the founder's teachings). I see a fundamental contradiction here.

Granted, I do not think Aikido is meant in any way to deal with uncommitted attacks, as these are more of a sportive environment thing. But tense or resisting force is something very important to work into training, especially for any art which intends to blend with the opponent's energy: you must have sensitivity training and the ability to adapt on the fly to do that.

Uncommitted attacks are not limited to a sportive environment. Anyone who knows what he's doing will not unbalance himself in a fight, it would be stupid to do so. Yet, aikido was able to deal with trained martial artists at some point in history. So, what happened?

I think it is the teachers fault, because teachers intentionally don't give their students energy to use. This is a great disservice to the student.

I believe that especially at first, teachers should intentionally give students a variety of committed, uncommitted, resisting, and unresisting force so that the student can learn to adapt to each of them.

Agreed, although at some point the student should take responsibility for his own training and try to find what's missing, because most teachers won't.

Sick pictures! Do you have the source?

Funnily enough that is one of the very unique things to Daito ryu and Aikido - traditionally in Japanese martial arts the teacher takes the role of uke. Takeda reversed this; he was by all accounts a hyper-paranoid, cantankerous old guy, who would never let anyone throw him.

Yep, although I suspect there were more didactic reasons for this, like conditioning uke's body by folding him like a pretzel, and making him feel that he's not being overcome through power.

I think alot of what we see as "Borrowing and blending" with an opponent's energy is Fake and completely inaccurate. I believe that both exists, but not in the way that it is often demonstrated. If you want to see accurate examples of "Borrowing and blending" with an an opponent's energy then watch people who actually use it.

Demos are great to watch, but the proof is sparring. Not trying to be disrespectful, but if your skills are this good, then it would be easy to sign up and win Push hands competitions and wrestling competitions. Or at the bare minimum on strangers

One of the things I often took advantage of is demonstration Jow Ga on non-students. This gives people an accurate idea of my ability at the minimum. One day I was training in the part and a Father and Son saw me training. The father was TMA fan. His son was an MMA fan. So I asked his son, what does he like about MMA. His son was a big teenager. So I gave the son an opportunity to take me down. My purpose wasn't to show the son that he couldn't take me down. My purpose was to show him that his idea of how he saw MMA wasn't as easy as he thought. So we get into the ready position. I told him I would not resist. I got into a low fighting horse stance. The son didn't try to take me down. I ask him, why didn't he try to take me down. He said because I was too low.

I enjoy doing things like this because it pokes holes in the assumptions that people have about TMA. They sometimes expect to see magic but are more impressed when they see it's not magic. His son didn't join the school that day, but his dad was able to walk away with bragging rights for his passion about TMA lol. If I only demo against students then people will say that my students let me.

Exactly.

Well, I wouldn't say that sparring is the only way, but a very good one for sure.

It's good to work on things in gradual steps of difficulty and speed, as well as control/freedom, because sparring with too much pressure all the time can rob one of opportunity to develop certain attributes, especially when it comes to feeling. At the same time, never sparring is even worse.

Flow and sensitivity drills, and mixing in non-compliance can be a useful training aide. Again, the FMA teacher I mentioned would often, during basic drills, switch between compliant and non-compliant randomly during basic drills to show the student what can go wrong and how to adapt. I found that approach really interesting.

I remembered that other quote from Mochizuki but couldn't find it (readily) onlineIt's not surprising that he'd make that comment, I believe that he had training in Katori Shinto Ryu.

In Morihei Ueshiba's aikido, uke does not do the overhand chop in basic techniques. Tori initiates with a metsubushi strike to the face, which leaves uke in the position where ikkyo can be applied. Morihiro Saito spent his life teaching it that way and some gave him crap with the whole "there's no attack in aikido" mantra. Then someone once brought him a technical instruction manual realised under the founder's supervision, where the technique was done Saito's way. As you could imagine, he was beaming, and from then on he'd bring the book with him at seminars and show people, like "see? I'm not making that up!".

I've seen ippondori (a DR technique resembling aikido's ikkyo) done against a downward sword strike in a DR video. However, both DR and aikido techniques are done (and taught) empty handed. Ueshiba had no formal training in weapons (apart from his bayonet training while in service, and he was very good at it) and there's no record of him ever fighting someone while being armed himself.

The weapons retention theory is most likely a rationalisation by later generations to explain why their techniques don't work in hand-to-hand combat.

I think that it's true that most aikidoka today couldn't make it work without experience in the styles you cited. I also think that, historically, this was not the case. World class martial arts practitioners (Kenshiro Abbe, Minoru Mochizuki, Shoji Nishio, Kenji Tomiki, etc.) went to study under Ueshiba whose only significant training was "aikido" (that is, DR). Plus, among Ueshiba's famous "fighters", several had little to no previous martial arts experience (people like Tohei and Shioda had done some judo in highschool, while Tadashi Abe started aikido at 16 with no experience, for example).

Given that Ueshiba and his students gained pretty impressive functional ability from their aikido training, it's worth asking oneself what they were doing differently. Ellis Amdur provides some interesting leads here: Great Aikido —Aikido Greats – 古現武道

This is a good way to understand the techniques from an external perspective and pinpoint similarities. Yet, without a solid technical foundation (gained through extensive training under a good teacher, and ideally supported by technical material from all-time greats) you'll likely miss the why of the movements. I also feel that solid historical knowledge about the art is useful to avoid baseless interpretations (like the weapons retention argument above).

In order to understand aikido, one has to understand fundamental principles like irimi: “Irimi,” by Ellis Amdur – Aikido Journal

Anyway, if you want to analyse aikido techniques that are as close to their original form as possible (although aikido is not about technique) I recommend looking at the Iwama (under Morihiro Saito) and Yoshinkan (under Gozo Shioda) lines of aikido. They are all-time authorities in terms of technique (although in his later years Shioda's demos shifted from techniques to body principles, which is actually good in terms of aikido).

Shioda could also pop your head out of alignment to make you fall, daito-ryu style (the whole video is good in terms of body movement, but the moment I've just mentioned is around the 2.40 mark):

Yep, it's in daito ryu. We also have it from the back:

Unfortunately, these techniques are trained less and less. I've never done ganseki otoshi because nobody in the dojo would be able to take the fall.

Agreed. According to the art's founder, aikido's purpose is "takemusu aiki" or spontaneous martial technique. Yet, aikido is one of the less spontaneous existing martial arts (and this also goes for lines like Iwama style that purports to stick closely to the founder's teachings). I see a fundamental contradiction here.

Uncommitted attacks are not limited to a sportive environment. Anyone who knows what he's doing will not unbalance himself in a fight, it would be stupid to do so. Yet, aikido was able to deal with trained martial artists at some point in history. So, what happened?

Agreed, although at some point the student should take responsibility for his own training and try to find what's missing, because most teachers won't.

Sick pictures! Do you have the source?

Yep, although I suspect there were more didactic reasons for this, like conditioning uke's body by folding him like a pretzel, and making him feel that he's not being overcome through power.

Wow, a real wealth of knowledge and research here!

I'd love to do Aikido again some day with someone who has true depth and breadth of knowledge, and isn't afraid to experiment with it. That is, if my wrist tendons ever heal (from typing).

I bolded and underlined a really important point you made, which I feel worth emphasizing. I also believe that to a large degree, it is up to the student to really "discover" and learn to use the art they study. It's a lot like learning a language, I feel: you can't become fluent just by showing up for class or doing exercises in a textbook. You have to gain experience and understanding that only comes with actually using and discovering it for yourself (to a level of both depth and breadth that goes far beyond what you can feasibly learn in a classroom, and in essence, requires you to "re-experience life" in a new language).

Everything is about technique. I would never train a martial arts or anything else thinking that "It's not about technique" That's a good way of training a lot of stuff that doesn't work. Which is probably why so many people who train Aikido aren't able to use it.Anyway, if you want to analyse aikido techniques that are as close to their original form as possible (although aikido is not about technique)

This is pretty solid in terms of understanding a martial art. I use this same method for learning Jow Ga kun fu and for understanding how my opponents may attack me. This way I always understand a technique and the context in which is used. Which is definitely a problem that Aikido has as there is no agreement on the context in which the techniques are used.This is a good way to understand the techniques from an external perspective and pinpoint similarities. Yet, without a solid technical foundation (gained through extensive training under a good teacher, and ideally supported by technical material from all-time greats) you'll likely miss the why of the movements.

A simple chopping motion sends Aikido practitioners into a whirlpool of debate where there is no agreement on what the motion is. This didn't just start in our time. This seems to be a long rooted problem that is affecting the function of Aikido. In other martial arts it is clear what the attack is. In Aikido it's not clear. If you can't agree on what the attack is then there's no way to offer a functional response. If you don't know what the attack is then how do you know that movement initiates the response that you need?

I will check these out as they may clear up what I seeI recommend looking at the Iwama (under Morihiro Saito) and Yoshinkan (under Gozo Shioda) lines of aikido. They are all-time authorities in terms of technique (although in his later years Shioda's demos shifted from techniques to body principles, which is actually good in terms of aikido).

This has been my experience with NGA, as well. Too much resistance too early leads many students to miss how techniques work and focus on muscling them (which can work with some techniques against someone weaker or less athletic). Lack of non-compliant training (no sparring) creates a whole range of issues in nearly all students. There may be other ways to prevent both sets of issues, but I haven't found them.It's good to work on things in gradual steps of difficulty and speed, as well as control/freedom, because sparring with too much pressure all the time can rob one of opportunity to develop certain attributes, especially when it comes to feeling. At the same time, never sparring is even worse.

I think the "it's not abourt technique" here is not the same thing you're thinking about. I have the same view about NGA. The techniques in the classical NGA curriculum contain some that don't make sense if you're looking at them for direct application. But if you look at them as drills for developing attributes, they make more sense. The concept is to develop specific attributes (specific approaches to movement, control, feel, etc.), and be able to apply them in a fluid fashion - no longer dependent upon specific techniques. In the past, I referred to this as "the grey space between techniques".Everything is about technique. I would never train a martial arts or anything else thinking that "It's not about technique" That's a good way of training a lot of stuff that doesn't work. Which is probably why so many people who train Aikido aren't able to use it.

The issue is that some folks then stick tightly to those techniques (I've actually even heard instructors saying that the further application got from specific classical techniques, the less good it was). The folks who are best able to apply their training (either in dojo or in practical application in their work) are those who recognize the principles and attributes, and are able to apply them without needing the specific techniques. Of course some techniques do have good direct application, and recognizing the difference is important. Otherwise, students (and instructors) can spend a lot of time trying to find direct function from an indirect drill. It'd be like a boxer spending hours trying to figure out how to use speedbag technique or jumprope footwork (kept close to the "speedbag form" and "jumprope form") in a fight. I've actually changed to using the term "form" instead of "technique" in some places to remove some confusion.

Steve

Mostly Harmless

Okay. Not trying to be argumentative, but can you explain how your story illustrates this? I mean, you said the kid didn't even try to take you down. Even if he had, how does this anecdote illustrate borrowing and blending? Either I fundamentally don't understand borrowed force and blending flow, or I don't understand how intimidating an untrained youth illustrates these concepts.The purpose of me posting the video was to show how Borrowed Force and Blending Flow works. I specifically showed the child so that people can see this stuff isn't magic that needs 10 years of training to achieve. Borrowed Force and Blending as nothing to do with your opponent's skill level. It's still a skill set regardless of how advanced or inexperience your opponent is. It is not your fault or concern if your opponent is not as good as you.

Learning from folks who actually use that thing is generally a good idea, regardless of what that thing is. I completely agree, though when certain guys talk about self defense, folks tend to forget this bit of common sense. But I think that the skill level of your opponent does matter, provided the goal is to continue to learn and progress in that skill set. Can you explain why you think it doesn't matter? Maybe I just have a different idea of what the goal is.Borrowed Force and Blending Flow seen with older wrestlers. Point of the story. If you really want to know Borrowed Force and Blending then learn from people who actually use it.

Ok here's the problem that I have with this. I get and understand the concept lesson, not the specifics of it, but just that it's a concept lesson. The part that I'm confused about is that.Shioda could also pop your head out of alignment to make you fall, daito-ryu style (the whole video is good in terms of body movement, but the moment I've just mentioned is around the 2.40 mark):

NO ONE, will hold onto you that strongly in application. The things that were shown were things that occur when someone holds onto you and doesn't let go. Chin Na and other grappling systems solves this problem by holding down their opponent's hand so that they cannot release it. Aikido Borrows Force and Flows with it. Your opponent will do the same thing. I see a lot of things in Aikido where the person is holding on for dear life. But in real life no one is going to hold onto you like that unless you are trying to pull out a knife or sword and your opponent is trying to keep you from doing so.

If you watch grappling you will see a series of holds in releases as they understand that holding can sometimes be worse than letting go.

This here to me is what I see as technique as well, which is why brute forcing techniques don't work.The concept is to develop specific attributes (specific approaches to movement, control, feel, etc.), and be able to apply them in a fluid fashion

This doesn't make sense to me, because the most physical things, you don't understand the principles and attributes until you apply them.The folks who are best able to apply their training (either in dojo or in practical application in their work) are those who recognize the principles and attributes, and are able to apply them without needing the specific techniques.

I can talk concept to you about how to ride a bide and keeping balance and shifting weight, but you really won't understand until you actual try to ride a bike. I don't understand how you can separate it from the technique (actually doing the technique). To me all of this is part of the technique. They are not separate things, because the technique cannot work without understanding (what you are talking about) in the context of applying the technique.

O'Malley

2nd Black Belt

Everything is about technique. I would never train a martial arts or anything else thinking that "It's not about technique". That's a good way of training a lot of stuff that doesn't work. Which is probably why so many people who train Aikido aren't able to use it.

If the goal of training aikido were to learn a technical curriculum (= a set of forms) this statement would be true. It's not. Aikido is a martial conditioning method based on Morihei Ueshiba's cosmology and supposed to make both body and mind stronger, which uses a selection of drills, jujutsu techniques and tactical principles as case studies to express these attributes but is not limited by them.

This is pretty solid in terms of understanding a martial art. I use this same method for learning Jow Ga kun fu and for understanding how my opponents may attack me. This way I always understand a technique and the context in which is used. Which is definitely a problem that Aikido has as there is no agreement on the context in which the techniques are used.

What you lack is precisely context. I don't mean to be offensive, but you lack the background to understand aikido. You have not been taught the principles of the art nor its technical details from a qualified instructor. You don't know the art's history and the context and purpose of its teachings.

You've seen it with the yokomen strike. Without hearing from a teacher that it's supposed to simulate a lateral sword strike, would you have considered that application? Without knowing that aikido comes from sumo, would you have considered the idea that the yokomen strike may in fact come from sumo's lateral palm strikes?

See also at 3:32:

I can guarantee that, without knowing that Ueshiba repeated ad nauseam that aikido is first and foremost about yourself, without knowing about his understanding of "in" and "yo", without knowing what "standing in six directions" or "standing on the floating bridge of heaven" means, you'll miss the meat of the art. When Henry Kono asked Ueshiba “Why can we not do what you do, Sensei?” he answered “Because you don’t understand In and Yo.”

This is a fundamental exercise in aikido, do you have any idea of its purpose?

The following three exercises were invariably part of each lesson under the founder in Iwama, do you know what their point is?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cBFZgBpSukg

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sF0diFgJEAQ

Please don't get me wrong, I don't mean to be pedantic (and many highly ranked aikido practitioners could not answer these questions, but this is another debate). My point is that, although your interpretations will probably make sense from a Jow Ga point of view and can be very valid from a martial perspective, they will differ wildly from what aikido was intended to be when it was created.

Ok here's the problem that I have with this. I get and understand the concept lesson, not the specifics of it, but just that it's a concept lesson. The part that I'm confused about is that.

NO ONE, will hold onto you that strongly in application. The things that were shown were things that occur when someone holds onto you and doesn't let go. Chin Na and other grappling systems solves this problem by holding down their opponent's hand so that they cannot release it. Aikido Borrows Force and Flows with it. Your opponent will do the same thing. I see a lot of things in Aikido where the person is holding on for dear life. But in real life no one is going to hold onto you like that unless you are trying to pull out a knife or sword and your opponent is trying to keep you from doing so.

If you watch grappling you will see a series of holds in releases as they understand that holding can sometimes be worse than letting go.

I agree, it's a concept lesson. The reason why uke holds so strongly is to make sure that tori is not muscling through the technique. In practice, if uke lets go or holds floppily, tori has a free hand to strike or grapple. When strikes are involved, for example, wrist control can be an important factor:

Aikido borrows force and flows but does not rely on this more than any other martial art (e.g. judo). Basic techniques are trained from static situations.

Last edited:

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 46

- Views

- 5K